Julianne Burke

Julianne Burke

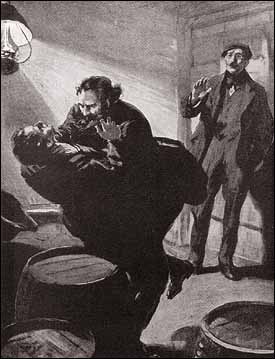

"Maybe you are in a humour for a fight, Mr. Boarder?"

"That I am," cried McMurdo."

"He hurled him across one of the barrels."

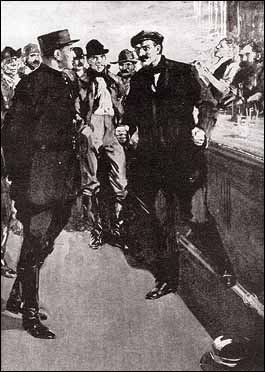

"I know a Chicago crook when I see one."

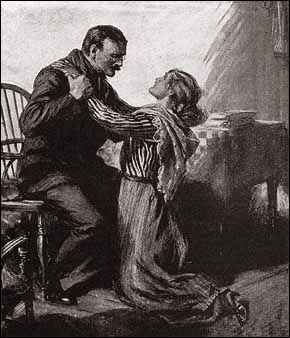

"Give it up, Jack! For my sake."

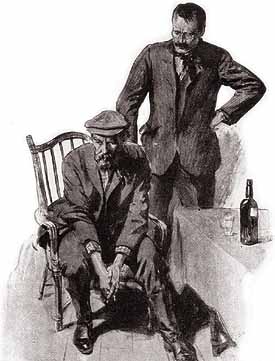

"There's a detective on our trail."

Illustrations by Frank Wiles

The Strand Magazine, 1915

What Really Happened in The Valley of Fear

and the Other Side of the Story

presented by Julianne Burke

notes by Carla Coupe

The Red Circle of Washington met at the Hyatt Regency Bethesda for an enjoyable evening of food and fellowship. Our guest speaker was Julianne Burke, who came to us from her home turf among the Pennsylvania coal fields that served as a stage for The Valley of Fear. It was a treat to welcome a Sherlockian who quite literally has that valley in her blood.

After kicking off her shoes and getting comfortable, Julianne introduced Red Circle to the real story of The Valley of Fear. She admitted that it’s not necessarily everyone’s favorite story for several reasons: with the flashback, Holmes isn’t in half the novel; and structurally it’s two separate stories, with a depressing ending. However, Holmes is at his best in the story, regaling us with brilliant deductions and even being reasonably sociable (for Holmes). It’s a strong story that includes a cipher and provides a lot of background information on Holmes’s nemesis, Moriarty.

In the ’40s and ’50s, both John Dickson Carr and Anthony Boucher were proponents and fans of the story. They pointed out that both parts are elegant detective stories in and of themselves. In fact, Birdy Edwards could be considered the first hardboiled detective.

Burke expects season 4 of the TV show Sherlock to contain elements of The Valley of Fear, especially after Jim Moriarty popped up at the end of season 3. This season may lead in with parts of The Valley of Fear and “His Last Bow.” She pointed out that the two stories are well paired, because in “His Last Bow,” Holmes follows the tactics Birdy Edwards used in The Valley of Fear.

She went on to compare the story with real-life events, asking ‘why is the story important?’ The novel is based on a series of events that took place in eastern Pennsylvania, the area where Burke grew up. Only a day trip from the DC metro area, visitors have a great opportunity to tour a place referenced in a Holmes story without a flight or the expense of international travel.

In reality, the fictional Scowerers were known as the Molly Maguires. Burke showed a map of local incidents—killings, unrest, hangings—that were associated with the Molly Maguires. Many of the area’s residents are descendants of the original 19th-century Irish immigrants, and there still exists a strong Irish nationalist sentiment. The Molly Maguires are considered local heroes; after all, as Burke said: one man’s terrorist is another man’s freedom fighter. At the time of the story, anyone who was a member of the Ancient Order of Hibernians was assumed to be a Molly Maguire, and the combination of membership in the Ancient Order of Hibernians and the word of a Pinkerton agent was enough to get a man hanged.

Conan Doyle got the idea for the bones of the story from a visiting Pinkerton agent, based on a popular propaganda piece by the Pinkertons and the industrialists who paid them. As Burke reminded us, history is written by the victors, and the victors certainly took advantage of that fact in this case. While the Pinkertons demonized the Irish at the behest of their masters, the Molly Maguires set aside privilege and empathized with the oppressed, including recent immigrants. These immigrants were fleeing the potato famine of 1845-52, when an estimated 1-2 million people died from hunger and related illnesses, and they brought with them a tradition of agrarian violence. The lack of any legal recourse to redress injustice often fueled these uprisings, and the immigrants were used to taking the law into their own hands.

The idea of the Molly Maguires was imported to the US in the 1840s from County Donegal. Irish immigrants encountered a lot of prejudice and were limited in the jobs they could get. Mining was open to both adults and young children, but conditions in the mines were terrible. The Molly Maguires fought for better working hours and safer conditions, as well as increased pay. One of their tactics was the use of strikes and violence.

The first unions were established in 1868, much to the displeasure of the industrialists. In 1873, Allan Pinkerton’s agency was in need of work, and he offered his services as labor spy and union buster to Franklin Gower, of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad. Gower was expanding his empire by buying mines and he wanted to break the unions. According to Burke, the Pinkerton agents took their mission seriously and were responsible for causing many deaths, both directly and indirectly, although at the time many of these deaths were attributed to the Molly Maguires.

The character of Birdy Edwards was based on Pinkerton agent James McParland, who was good at saving property, but not lives. Paralleling the fictional scene where Birdy confronts Boss McGinty, McParland confronted Black Jack Kehoe in reality, and the tragic upshot was that 20 men were hanged, many of whom were probably not guilty. Gower ensured the outcomes of the trials by appointing a special prosecutor and paying prosecution witnesses, while some defense witnesses (even including the wives of the accused) were jailed for perjury, often with no concrete evidence. Many were convicted on the strength of ‘personal confessions’ to McParland. Burke considers McParland an agent provocateur. He and his associates, including McParland’s brothers worked undercover, and while they could have saved the lives of many innocent people, they instead chose to sacrifice them to catch the Molly Maguires in action. Their actions helped crush labor unions for over 20 years.

Burke provided several postscripts to the events discussed: Gower eventually went bankrupt and committed suicide; in 1907 McParland repeated the tactics he had used against the Molly Maguires on another case, and at the trial, the noted lawyer Clarence Darrow exposed him as a liar and psychopath; and Black Jack Kehoe was tried and hanged, receiving a pardon ten years later, for all the good it did him.

Finally Burke asked: was justice served? Her answer: McParland was no Birdy Edwards. She provided a fitting coda to a tragic era in our country’s history, despite the way in which fiction white-washed the facts.

The Red Circle will convene again on Friday, March 18, 2016.